Darlings,

I have aspirations for my bedside table: I dream about it being an emblem of English femininity, a Nancy Mitford-esque tableau, charmingly chic like it was when I was a teenager. When I reached the age of fourteen I was finally allowed a bedroom that was separate from my beloved twin sister Lucy after I had thwacked that dear sib on the head with a heavy, leather-bound volume of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica, almost concussing her. My new bedroom was a heavenly escape from my five other darling sibs, and I was obsessed with every detail of its décor.

I adored the little bamboo chest next to my bed which was lit by a chintz-shaded lamp and a Bougie Rigaud candle if my mother had been on a work trip to Paris and brought one back for me. (That zebra-print box, the blue satin bow, forever glamourous, takes me straight back to my 1980s childhood.) I had all the time in the world to artfully arrange and re-arrange the surface of this bedside chest with things like old perfume bottles (all empty as these were purely for decoration), wildflowers gathered from the hedgerows, marbled notebooks purchased on vacations in Florence, a fountain pen for scribbling in my diary and most importantly a hard backed novel by, say, Anita Loos or Vita Sackville-West which I’d filched from my grandmother’s bookcase. It goes without saying that the books had to have an alluring jacket to qualify for a placement on the bedside table, but, Dear Reader, unlike the perfume bottles, the books were not just for show: the contents had to be as beautiful an experience for the mind as the jacket was for the eyes.

Things have deteriorated. Now, I’m ashamed to admit, my bedside table is often a dreadful swamp of abandoned ARCs, manuscripts and recently published books. There are also frequently piles of the aforementioned on an upholstered stool next to the bed; these inevitably slide onto the floor; two armchairs by the fireplace are often impossible to sit on because of the books which I have discarded in a fit of despair. This is because I am ridiculously fussy when it comes to my reading: I guess it isn’t a surprise that as an author I enjoy well-written sentences, beautifully constructed paragraphs, immaculate grammar, skillful pacing, brilliant storytelling and vividly drawn characters and I would be lying if I said that I feel much contemporary fiction satisfies even half of those criteria. Like all of us, I am in the market for newness, whether that be fashion, television, art or literature, but over the past few years I have read only a handful of new works that I would define as outstanding. I wish there were more books of the quality of Andrea Elliott’s Invisible Child, Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain and Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age.

The sad truth is that the terrible state of my bedside table and surrounding area is the result of me rejecting most of the new books I try by about chapter two. I even abandon some by paragraph two, being of the ruthless opinion that if you didn’t grab me on page one, you never will. I say this with the experience of having been tortured by my long time editor, Jonathan Burnham, who made me rewrite the first paragraph of my first novel, Bergdorf Blondes, over and over again until it was a perfect piece of comedy. He pretty much locked me in a room next to his office for five days while I redid that opening, having explained to me at the beginning of the week that he was the kind of editor who suffered from ‘a severe case of First Paragraph-itis’. I thank him to this day for the torture, and I still love the way that book opens.

All of the above are why, as a huge reader and someone who sees a great book as an experience unparalleled within the arts, I tend to go back again and again to the classics, whether it’s Henry James, Edith Wharton, Evelyn Waugh, Truman Capote or P.G. Wodehouse, for the kind of writing that nourish the brain and soul. Books like Portrait of A Lady, The Age of Innocence, Brideshead Revisited, In Cold Blood or Thank You, Jeeves (my favourite Jeeves novel) never get old, not just because the quality of the writing is sublime, but also because the social observation and historical depth add layers that are deeply satisfying and illuminating.

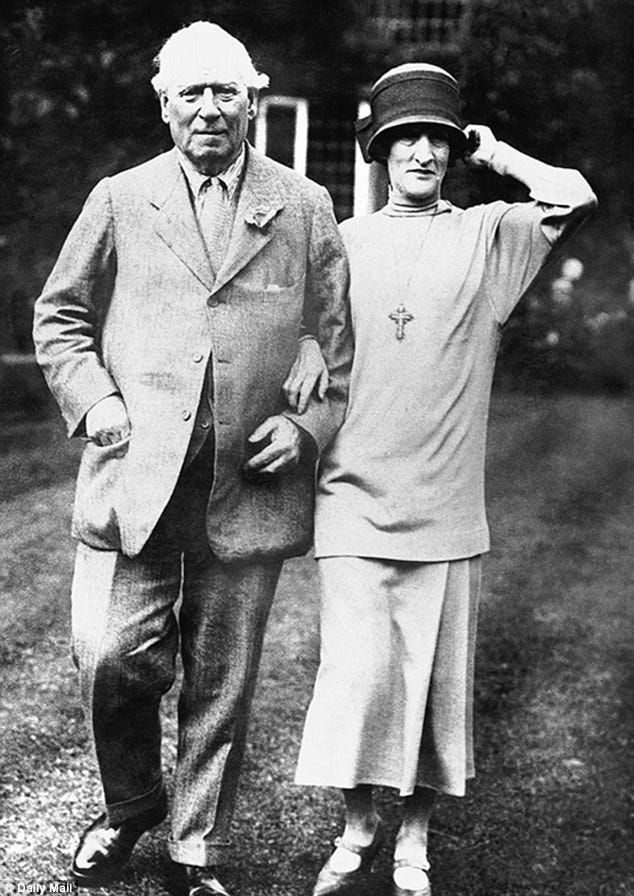

This is a long way round of saying that when I do occasionally land on a new book that resonates, I get absurdly over excited. One such book is Robert Harris’ latest, Precipice. I had been recommended this book several times over the last few months, even been given it, but it had sat by my bed unread, buried in the awful pile described above. Stupidly, I had allowed the jacket illustration of a rather Churchillian figure with a woman in the background to swerve me away from it. Together with the title, it all seemed terribly male and I couldn’t quite understand why my friends were raving about this book until someone explained the subject matter: the author had woven the true story of an infatuation between the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith (b.1852-d.1928), who presided before and during the First World War, and aristocratic beauty Venetia Stanley (b.1887-d.1948) into a grand historical novel. I was intrigued.

What a joy then, to dive into this book and find myself virtually unable to put it down. This book is so well written, so technically brilliant, and has such an incredible storyline that I was literally dying for bedtime to come so I could carry on reading each night. The story of Herbert’s obsession with his daughter Violet’s best friend, Venetia, is extraordinary. He first laid eyes on her when she was nineteen, and he was fifty-four, and for several years between 1910 and 1914 met with her every week in the back of his ministerial car, sharing classified secrets and telegrams with her during those meetings while they would drive through the London parks with the blinds down. When war broke out in 1914, Asquith wrote to Stanley incessantly at her family’s estate in Wales where she was based, sometimes as often as three times a day, frequently during Cabinet meetings, and even included details of troop movements and state secrets among his declarations of love for her. He visited her at the family estate on the flimsiest excuse, often with his wife and children in tow, despite being in the depths of a disastrous and spiraling war. By the spring of 1915, Venetia found the pressure too much and accepted a proposal of marriage from Edwin Montagu, one of Asquith’s protégés, prompting Asquith to write to Venetia’s sister, Sylvia, three times on the day he heard about the engagement. When Asquith left office he burned all his personal correspondence, but Venetia kept the hundreds of letters from Asquith, which were discovered in the 1980s. Harris has skillfully woven Asquith’s original letters into this novel, writing imagined letters back from Venetia. It’s a compelling setup for a brilliant work.

This is the most satisfying read I’ve had in ages. I studied history at university and it’s a joy to read something that brings the diplomacy and machinations at the heart of a war government to life, as well as illuminating the human and emotional side of politics that is so rarely seen and often goes undocumented. The role of women in war is one that is both fascinating and neglected, having been barely recorded in official histories, and it seems that the novel is a way to explore this. Like many of her class, Venetia Stanley worked as a nurse in hospitals in London and France during the war, and this part of her life has reminded me how much I want to look more into the life of Edith Violet Gorst, about whom I know only a tiny amount. She was married to my great grandfather, the highly controversial figure Sir Mark Sykes, (see The Man Who Created The Middle East by Christopher Simon Sykes for a full biography) and during the first war, Edith set up hospitals for the war wounded first in Yorkshire, and later in France, funding and running them herself. I feel sure there is a fascinating story to uncover there, even the inspiration for a book, but finding information about women of the time is not straightforward.

Harris’ book reminds me of another outstanding historical novel, Cressida Connolly’s After The Party, which examines the impact of the Second World War on the wives of British fascist party members, many of whom were imprisoned simply for the crime of being married to men of the wrong political stripe during the war years. Beautifully written and executed, Connolly’s book is one of those forever novels that will never date or get old and feels even more relevant in the current political climate.

Now, you can guess what I need to go and do – tidy my chaotic bedside table, take any unwanted books to a charity shop (I can’t bear throwing a book away) and order Robert Harris’ backlist, starting with his book about the Dreyfus Affair, An Officer and A Spy, which I am told is riveting. I’ve no doubt it will qualify for a placement by my bed.

Au revoir my darlings!

XOXO,

Plum

I have a beautiful bed, dressed in the most delicious linen and muslin bedding I can afford. I make it every day and take great pride in how it looks, smells, and feels. The rest of the bedroom is equally beautiful and calm apart from my Bedside Disaster. Piles of books, discarded hair ties, chargers (ugh- the worst!), lip balm, scraps of paper with nonsensical words that made sense at 4 a.m., Mardi Gras tat that I can't bear to throw out, socks in case my feet get cold at night.... you get the idea. I leave the bedroom door ajar to hide it all.

Also, Pompeii by Robert Harris is outstanding. When I visited the ruins, even the guide recommended it as a valid historical account of the time.